Homework: Researching Your First FBI FOIAs [2017-09-27]¶

Attention

- Description

- Learn about FOIA and research techniques by figuring out whose FBI files have not yet been FOIAed

- Due

- 2017-09-27

- Slugline

None – Submissions won’t be through email.

Fill out this Google Form

Objectives¶

- Have our first (of many, hopefully) experience with making a public records requests.

- Getting acquainted with the technicalities of FOIA law

- Finding out what the FBI has on 2 (deceased) people in whom you’re interested.

- Learning to use research techniques (i.e. Google) to find and filter new ideas.

- Making structured data out of our collective FOIA requests.

Background¶

Most students haven’t made a Freedom of Information Act request, even though it’s a right that is as easy to exercise as using copy-paste and sending email. In fact, because other citizens’ requests are public record, copying and repeating that request is fair game, if you’re looking for your first-time FOIA to be a predictable experience.

However, most people, especially journalists, like doing something new and interesting – i.e. impactful – for their first dip in the FOIA pool, even as they’re trying to avoid getting caught up in the bureaucratic and political complexity of FOIA law.

For your first FOIA, make it a FBI File¶

Surprisingly, the U.S. Department of Justice has an offering for this choosy, entitled mindset: The FBI Files. I use the phrase FBI File as shorthand for the records the FBI collects and compiles – for whatever reason – on any individual person.

Now you can ask for your *own* FBI file, as Aaron Swartz did. Or for the FBI file for someone who has given you permission. However, these requests technically fall under the Privacy Act. So while it’s still a public records request, and jumps through the same hoop as a request under FOIA, it’s not technically FOIA. I only emphasize this detail to foreshadow just how annoyingly technical laws and records and data and politics can suddenly get.

And whether the request is FOIA or Privacy Act, there’s also the inherent possibility that you – or anyone who willingly lets you request their FBI file – may not be the type of person who the FBI collects files on, i.e. you and your close friends are boring. So even when the request is fulfilled, you might end up with a disappointing form letter about how you haven’t caught the FBI’s eye yet.

Instead of FOIAing for yourself, or for someone you personally know, FOIA the FBI File of a complete stranger. The one simple trick: the complete stranger has to be deceased.

The deceased individual doesn’t have to be related to or approving of you in any way. They just have to be dead. And you just have to produce documentation of the fact – this can be an actual death certificate, or something as ubiquitous and Googleable as a news report. This information can be pasted into the FBI’s offical sample letter, which you can then send via email.

Directions¶

Think of 2 notable and deceased individuals, who have not yet had their FBI File requested via FOIA.

Then fill out this Google Form so I can track who’s FOIAing whom, and get some structured data about the people in whom we, as a class, are interested.

Specifically, these 2 individuals must have these characteristics:

- Their death is part of the public record, preferably a news article.

- Their FBI file has not already been published by the FBI, e.g. on

vault.fbi.gov - To the best of your (and Google’s) knowledge, no one else has attempted to request their FBI file

Additionally, I’m imposing these 2 arbitrary requirements:

- This person must have died after 1940. The FBI’s records predate 1940. I just want to keep the scope of our class research relatively contemporary.

- This person must either be a U.S. citizen, or spent a substantial amount of their life in the U.S. Yes, the FBI had files on Saddam Hussein and Princess Diana. But the surveillance of citizens is enough spycraft for this exercise.

While “notability” doesn’t have an exact definition, please think of persons who are not either directly related to you or otherwise personally connected. You’re free to request FBI files for people you know on your own – as you’ll see, it’s literally just a quick email.

Discussion¶

It’s possible to simplify the work of this assignment as:

Find 2 famous people whose FBI files are worth FOIAing.

Now, depending how often you think about deceased people – notable and non-notable – it’s possible that you could think of 2 qualifying individuals within a few minutes and basically be done with this assignment. For the sake of discussion, pretend you don’t have that ability. Or pretend this assignment asked for 100 such people from each student, or some other ridiculous number that can’t be catalogued in your head.

Of course bulk FOIAing is not the point of this assignment, which is why I’m only asking for 2. But I do want you to approach this – even as it seems like overkill – in a systematic approach rather than random brainstorm.

Morbid, but computational heuristics¶

Let’s revisit the simplistic summary of the assignment:

Find 2 famous dead people whose FBI files are worth FOIAing.

Even if this is an elegant summary, the requirements are stated in a way that imply more subjectivity.

- The person is dead.

- The person be “famous”

- The person’s FBI file is worth FOIAing

Dead is still dead. But people might disagree on how to judge “famous” or “worth FOIAing”. So let’s break these descriptive requirements into heuristics more computational. And by that, I mean, “stupid enough for a computer to process”.

Here’s one take:

- The person is dead

- The person is notable enough to be featured in a obituary published by a media outlet.

- If an existing reference to this person’s FBI file can be found, then this person’s file is not worth (formally) FOIAing.that has already been FOIAed is not worth (formally) FOIAing again.

- Someone who has recently died is less likely to have already been the subject of a FOIA.

Facing off against Parker Higgins’s death machine¶

ProPublica’s Scott Klein warned journalists back in 2014 that they “will be scooped by a reporter who knows how to program.”. And that’s exactly what programmer-activist Parker Higgins has done to you if you had hoped the NYT’s obit section would be your one-stop destination for FOIA ideas.

Because going to the NYT obit section would almost certainly be the easiest way to satisfy the proposed heuristics (dead, famous, recent). And in the early stages of his FOIA The Dead, Higgins had been checking out the NYT obits list and sending out FOIAs the manual and old-fashioned way. At some point, like a clever and sane programmer, he decided to write a program to automate the boring parts, including visiting the NYT obit site to look for names of famous dead people (if they’re in a NYT obit, then they’re all famous!)

Here’s how Higgins describes his work, in a April 2017 NPR interview:

SIMON: So you read an obituary in The New York Times, and then you send a Freedom of Information Act request?

HIGGINS: For every New York Times obituary since about November 2015 I’ve been doing that. And this started with me doing it manually - right? - with people I found especially interesting. And I realized that this problem was the sort that could be automated pretty easily. And really I think it’s important to do it that way because the most interesting file that I get back will be one that nobody expected existed.

You can see the results at the FOIA the Dead homepage. And you can see the paperwork – the requests, and how the FBI responds to them, on MuckRock, which Higgins uses to file the requests.

The interviews with Higgins about FOIA the Dead are worth reading, because it’s valuable and inspiring to hear from him what he’s learned from these files, i.e. why freedom-of-information laws are important to a functioning democracy and justice system:

- Finding FBI Files of the Dead, NPR Weekend Edition; 2017-04-01

- This Bot Files FOIA Requests to the FBI Whenever The New York Times Posts an Obituary, Newsweek; 2017-03-10.

- Project opens the FBI files on the notably dead, Star Tribune; 2017-04-12

- FOIA the Dead uses The New York Times’ obituaries to shine a light on FBI surveillance, for the living, Nieman Lab; 2017-03-15

However, the downside of his project is that for this assignment, you cannot use the NYT obit section to fulfill this assigment. Welcome to the world of automation-powered-unemployment!

Thankfully, there are some pretty easy ways to find what Higgins’s death bot cannot. And they’re as common-sense (And computational) as they seem.

Finding the newly dead without the NYT¶

Higgins’s program only checks the NYT obit section. Why? Maybe he’s a NYT-snob. Or his data plan is limited to 200KB a week. Or he’s spoiled by the convenience of how NYT’s developer platform. Either way, the opportunity is obvious for us. Look at other newspapers with obituaries. Some examples:

Of course, newspapers of similar size and audience will often write obits about the same people (probably one of the reasons why Higgins didn’t think it worth to collect obit info from another source). So for any given candidate on these other non-NYT sites, you need to check if that person has been written about by the Times (and thus auto-FOIAed by Higgins)

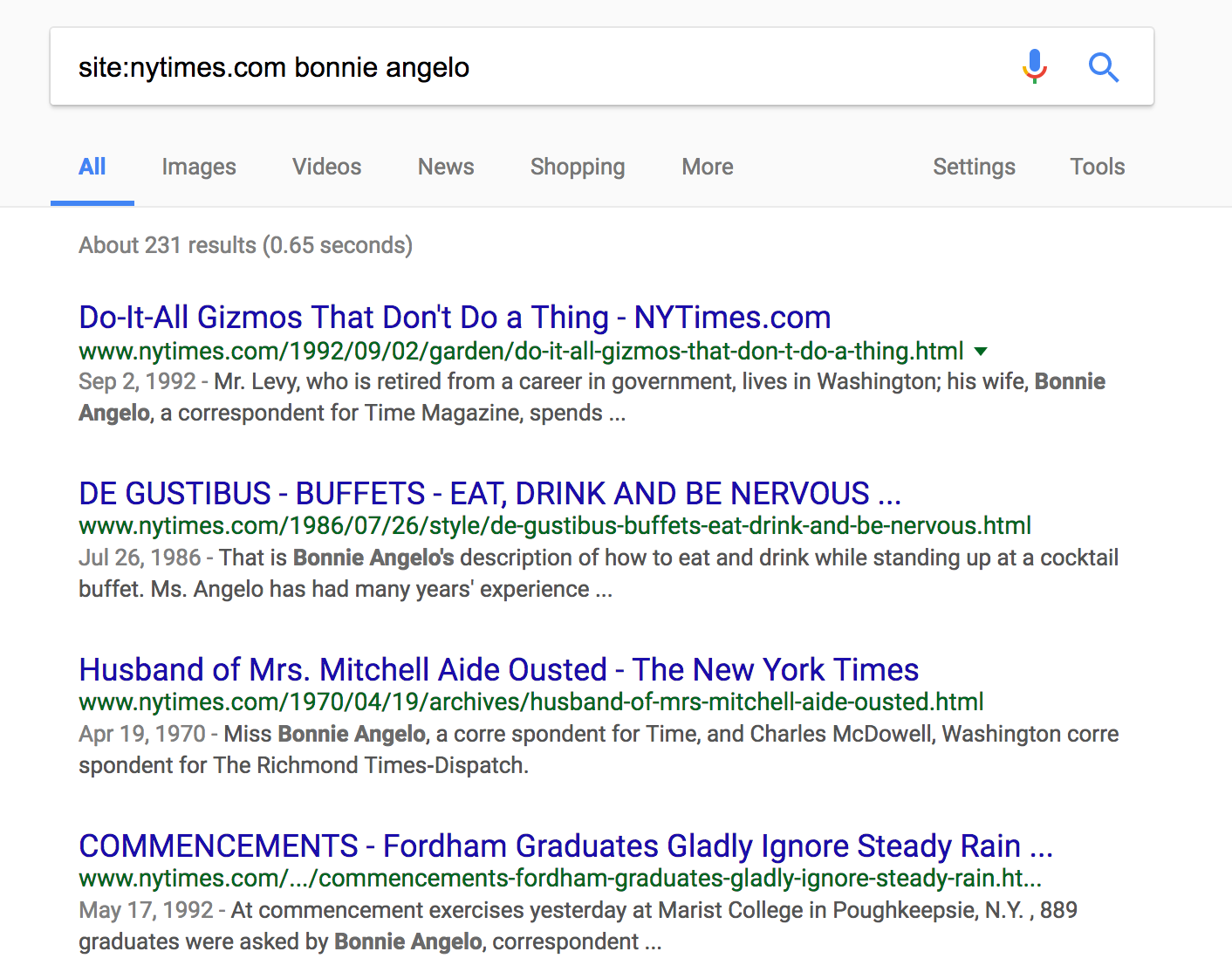

I recommend using Google and the site: search operator to check for a recent obit. For example, the Washington Post wrote about political journalist Bonnie Angelo.

Here’s the Google search to see if the NYT also wrote about her:

site:nytimes.com bonnie angelo

Doesn’t look like there are many recent or obit-related results for “bonnie angelo” on the NYT (…for now):

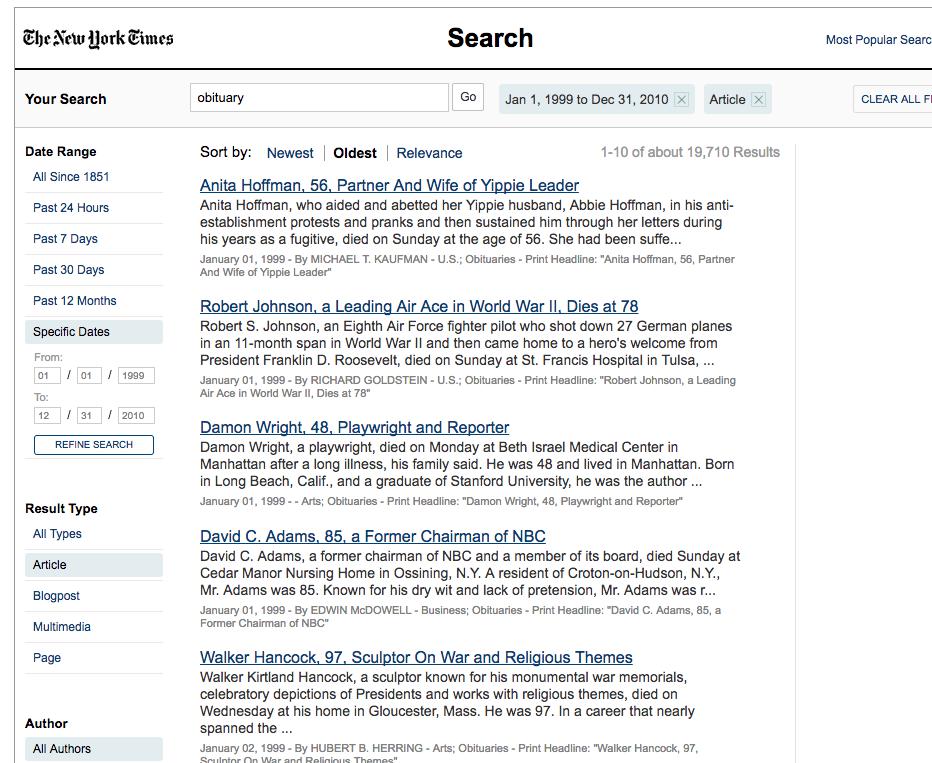

Finding the deceased in the past¶

According to the Star Tribune article (see? research is helpful), Higgins started “FOIA the Dead” in 2015. Doesn’t seem that the project has attempted file for pre-2015 obits. So we can use NYT’s site search to look for obits within specific dates, i.e. before 2015.

http://query.nytimes.com/search/sitesearch/

We don’t know the specifics of NYT’s search engine or article classification, such as all articles we would consider to be obituaries have that metadata (and whether that classification has been consistent over the decades). But a search for the term “obituary”, from 1999 through 2010, sorted by oldest publish date seems to return candidates whose FBI files have not been FOIAed.

The NYT has a great search engine, as so do some of the other large news sites (the pain point is usually taxonomy and organization). However, if you are on Stanford’s campus, or otherwise have free access to NexisLexis Academic, I highly encourage doing the same kind of historical “obituary” search on LexisNexis, which not only has a huge archive of newspapers, but also far more sophisticated query options.

You can view the LexisNexis tutorial from Padjo-2016: Using LexisNexis Academic to Search for Old News

Competing with the world’s FOIAers¶

It probably isn’t a surprise that if we expand our obit search for the years and even decades previous to 2015, we’ll end up with plenty of people who haven’t been FOIAed before. However, all heuristics have a tradeoff. And for including people who have died many years ago in the past, we are, by definition, including people who have had many more years to be noticed and selected for a FOIA request. Or even a FBI data dump, as they’ve done in the past.

Well, no one said heuristics were perfect. However, it’s worth considering the real world of FOIA requests and responses, specifically its history. FOIA was enacted in 1966. Computational record systems existed back then, but not to the degree or speed we have now. Even if we think today’s FBI handles FOIA with exceptional speed and grace, the flow of information back then may have simply been slower. The upshot as far as we’re concerned is: people who died in the past probably were less noticed by records requesters.

That said, even if you’ve found older notable folks who were less likely to have been the subject of FOIA when they died, we don’t live with their constraints. Making FOIAs is easier, and so are the many other verification techniques. Before you fill out the Google form for your FOIA-eligible person, let’s consider a quick way to check for existing FOIAs.

Speeding up our research/filtering with Google’s search operators¶

All of the above sites are useful and worth visiting for their own reasons. But we’re not interested in that. We’re interested in taking someone’s name, like “Bobby Heenan”, and seeing if any of those document-heavy sites have a related FOIA-request.

Dan Russell, Google’s top “anthropologist of search”, has a great homepage full of Google search resources. While Google’s special search operators change over time, Russell keeps an updated list of all the ones he knows about

The relevant operators:

site:example.com – restricts search results to the example.com domain

apples OR oranges – used to include alternative conditions for results, i.e. include results that contain either ‘apples’ or ‘oranges’

It depends on the name¶

It’s not always the case we have to think of fancy queries. If someone’s name is relatively rare, such as bobby heenan, then a query of bobby heenan foia will most likely bring up all the possible FOIA-related results, if they exist. In Bobby Heenan’s case, they do (thanks FOIA the Dead!)

https://www.muckrock.com/foi/united-states-of-america-10/bobby-heenan-fbi-file-43066/

Quote names with wildcards¶

Surrounding query terms with double-quotes will return only results with those exact query terms; e.g. "john smith" won’t return jon smith.

What happens if you’re searching for a “John Smith” but you don’t know if the documents will include his middle name or initial? Use the asterisk to indicate a wildcard match.

So while there maybe a high number of webpages that are valid results to the query for john smith fbi foia, far fewer pages will match "john * smith" fbi foia

Restrict the search to specific sites and domains¶

You may know how to use site:example.com something to search for something only on example.com. However, given that we know of several FOIA-heavy websites, doing site-specific search queries per query is so tedious that no one sane would do that much cross-checking.

Google Search’s OR operator specifies alternative terms to search for, i.e. stringer OR avon returns webpages with either “string” or “avon”. If you’re like me though you may not have know how to combine OR with site:.

If we want to search for kanye foia across both the muckrock.com and fbi.gov domains, the following query would return zero results:

kanye foia site:muckrock.com site:fbi.gov

We need the OR between both sites:

kanye foia site:muckrock.com OR site:fbi.gov

To search across all the previously mentioned FOIA-heavy domains, it’s just more typing:

kanye foia site:muckrock.com OR site:fbi.gov OR site:scribd.com OR site:documentcloud.org OR site:archive.org

One obvious problem for us is that for every person that we want to check on, we need to search across at least 3 different sites. Here’s where old-fashioned Google, with a few specific tricks, will save us more time than dealing with the search tools specific to FBI.gov, Muckrock, and Archive.org.

What’s not so obvious is that site: and OR can be combined.

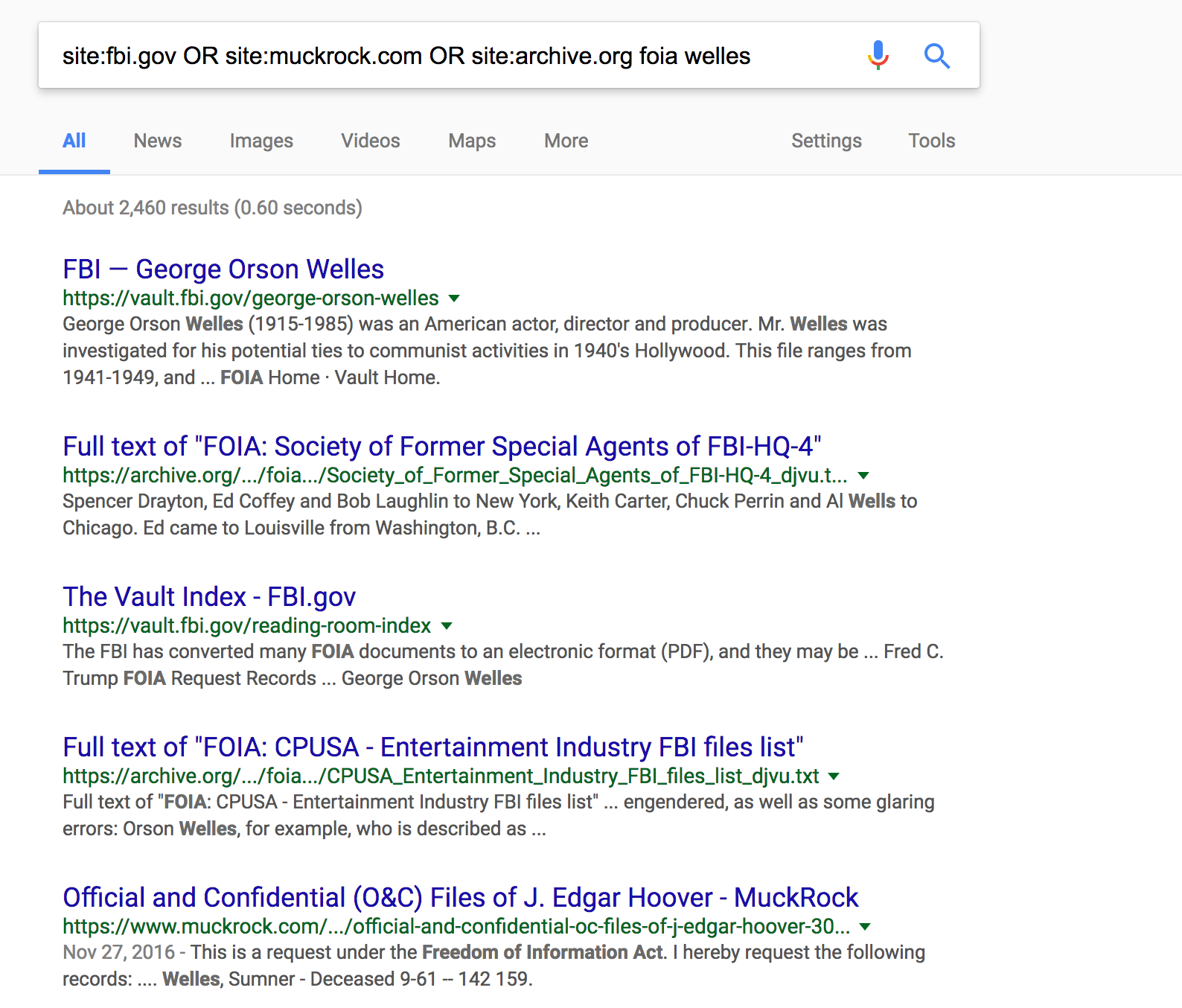

For example, the following 2 queries would return pages and documents relating to foia welles on fbi.gov and muckrock.com, respectively:

site:fbi.gov foia wellessite:muckrock.com foia welles

However, it’s tedious to do 2 Google searches just to confirm whether a search term appears on either site. Pretend that we wanted to retrieve foia welles-related results from both fbi.gov and muckrock.com. We would get zero results if we try this:

site:fbi.gov site:muckrock.com foia welles

Apparently, Google interprets this as a request for foia welles-related results that are simultaneously on fbi.gov and muckrock.com, which is impossible.

This is where OR comes in (OR must be in uppercase, or else Google will treat it as a literal word to search for):

site:fbi.gov OR site:muckrock.com foia welles

To include results from archive.org:

site:fbi.gov OR site:muckrock.com OR site:archive.org foia welles